Preventative conservation needs for works on paper

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Carley Roche, Associate Registrar

July 24, 2025

It’s not just humans and other living species that feel the damages of aging, but inanimate objects too. Tools can be overworked, metals can rust, works on paper crease and discolor, and objects made of organic materials such as wood and stone can naturally degrade. These damages can even cause the object to deteriorate to an irreversible point, leading to disposal. Just as with people, there are ways to care for these objects to ensure their long-term sustainability, even in the case of an accident or incident that causes heavy physical damage to an artifact. From proper storage techniques to professional conservators assisting in object preservation, there are many ways cultural institutions can help ensure the longevity of their collections.

This blog post focuses on the work of collections specialists and conservators in preserving paper-based works of art and artifacts, looking at the history and importance of conservation in cultural heritage. I will then specifically look at recent conservation work undertaken by the Museum to completely remove a selection of sheet music, ocean liner travel posters, and clipper cards from harmful plastic encasings.

Brief History of Conservation

Ever since people began creating, they also began repairing and preserving. Everything from natural environmental events to human error can cause destruction, but people will always find a way to ensure their culturally significant objects will remain.

Conservation is a broad term that is used by different disciplines including environmentalism, ecology, sustainability, and, of course, cultural heritage. Across these different studies, conservation always breaks down to the same ideas of preservation and protection. Within cultural institutions such as museums, art galleries, archives, and libraries, where artifacts, artwork, and documents are housed long-term, conservation ensures that individual objects, structures, and entire collections of artistic, historic, and cultural value are preserved for future generations.

Despite technically thousands of years of conservation work, the first graduate-level art conservation program in the United States was not established until 1960. Prior to this, conservators learned restoration techniques by studying specialized trades and completing apprenticeship programs.

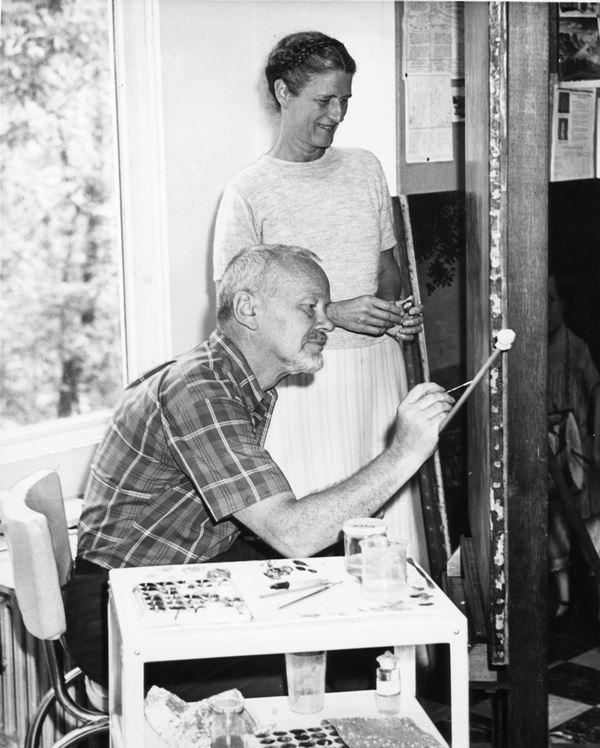

This first program began here in New York City at New York University as the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts thanks to Sheldon Keck (1910–1993) and his wife Caroline Keck (1908–2007) seen here.

Focusing on teaching students the basic properties of different artists’ materials and their deterioration process alongside art history, the training conservators were given a well-rounded scientific, technical, and artistic education.

Today, graduate-level art conservation programs follow similar curriculums to ensure that students have an understanding of art and artifacts on an individual level, as well as a collection from a specific time period, original location, artist, and their intention.

Photograph of Caroline and Shelden Keck. Brooklyn Museum Photograph Collection. S-06. Brooklyn Museum Libraries and Archives.

Modern conservation is a highly-scientific career path, with many conservators becoming an expert in a specific medium. Whether they choose to focus on sculptures, paintings, photographs, paper-based items, books, textiles, or other material, they all work within an ethical obligation to preserve and restore cultural heritage through extensive research and care. The American Institute of Conservation (AIC) has an established Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice that directs current and future conservators on how to approach projects.

Plastic: Protector or Destroyer?

A common material used for preserving documents, photographs, and small ephemeral pieces is plastic. This synthetic material is typically composed from the elements carbon, silicon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and chloride–however, plastics are not all made the same way. Depending on the source material—such as natural gas, oil, or coal—and the way materials are processed during manufacturing, you can get varying results of plastic and their uses[1]”Safe Plastics And Fabrics For Exhibit And Storage” Conserve O Gram, August 2004, Number 18/2.

When it comes to choosing plastics for the preventative conservation of artifacts and their storage, only three plastics fit archival museum standards: polyester film, polypropylene, and polyethylene.

These three plastics share one important similarity: they are all chemically inert. This means they will not have a chemical reaction when in contact with other materials, which is highly important for works on paper as inks, dyes, and the paper itself could be made of materials that can lead to oxidation[2]Oxidation is a chemical reaction in which molecular components of paper begin to weaken when exposed to oxygen, causing yellowing and decay..

Polyester film, known by its name brand Melinex and Mylar, is highly recommended for preserving works on paper: it is chemically stable, highly transparent, and has an inherent static electricity that keeps artifacts from moving around within a sleeve (as seen above)[3]It must be noted that due to this static charge, polyester film is not good for housing works of art on paper made with charcoal, pastels, chalk, or watercolors as these substances can easily lift … Continue reading. Polypropylene is recommended next, as it is heat resistant and good at protecting against moisture. Finally, polyethylene is recommended based on its soft, flexible nature, but it has a more clouded appearance than the two other plastics.

While these three plastics are well-known in cultural institutions today for their multiple preservation qualities, it was not known until recently that other widely-used plastics could be damaging to art collections.

One of the most widely used plastics that is now understood to be damaging to historic artifacts is polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Used in everything from children’s toys to plumbing pipes, PVC is manufactured with additives known as plasticizers, which make it more flexible and durable.

However, PVC is also highly reactive and unstable—once it begins to break down, it does so quickly. During its deterioration process, this plastic off-gases hydrochloric acid, causing harmful damage to any artifact it touches or that is stored nearby.

Photo by Rob French. Museums Victoria blog post “Our addiction to Plastic“.

If you are storing paper-based materials in plastic sleeves and you notice a vinegar smell, yellowing of the plastic, or a waxy sticky substance on the surface of the sleeve, it is time to find a new archival-quality plastic housing for your objects.

Delaminating the Past

From the 1930s to the 1980s, lamination was a popular method used to preserve paper-based artifacts as a way to protect works on paper from dust, pests, scratching, and water damage. This is mainly due to the 1934 report from the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), which recommended this process for conservation treatment because it was cheaper than the previously, popularly-used silk lamination process, and the plastic encasing was also believed to strengthen the paper artifact.

The lamination process involves placing a paper-based artifact between two sheets of plastic with a chemical adhesive used to secure the plastic sheeting around the artifact. All of these pieces would then be heated and passed through rollers with great pressure to fuse the plastic sheets around the document.

Left: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, [LC-DIG-hec-27704].

Right: Modern lamination machine.

The process involves using unstable plastic that can cause heat damage to paper, and the possibility of creating a microclimate between the document and plastic sheets that is perfect for mold growth. So, you can only imagine the distress that this process could cause to any cultural heritage worker. Here at the Seaport Museum, Collections and Archives staff and interns often encounter similar lamination treatments, whether during ongoing inventory and imaging projects, or during exhibition preparation.

Knowing that any in-house attempt to remove the plastic could cause irreparable damage, including lifting of ink off the paper, static cling, tears, and more, we recently began selecting objects to be delaminated by professional paper conservators. After several on-site visits by professional paper conservators from Alvarez Conservation Services to review the various laminated objects, they advised us to bring a selection of artifacts to their studio for delamination. Alvarez has been a trusted conservation studio for over 40 years “specializ[ing] in the conservation treatment of a wide range of art on paper: drawings, watercolors, pastels, gouaches, oils, books, documents, manuscripts, and all types of prints.”

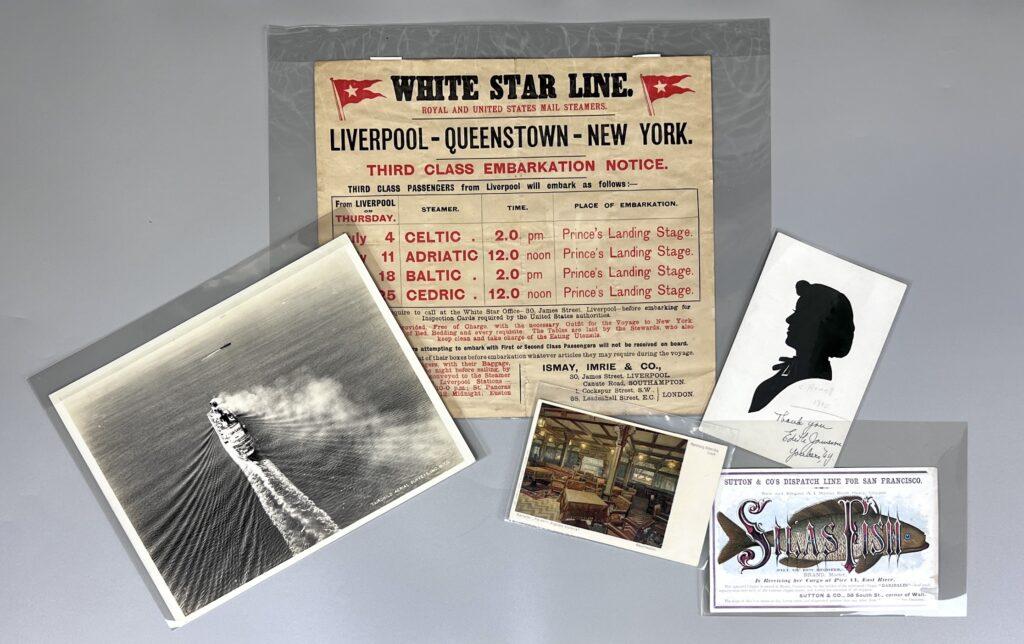

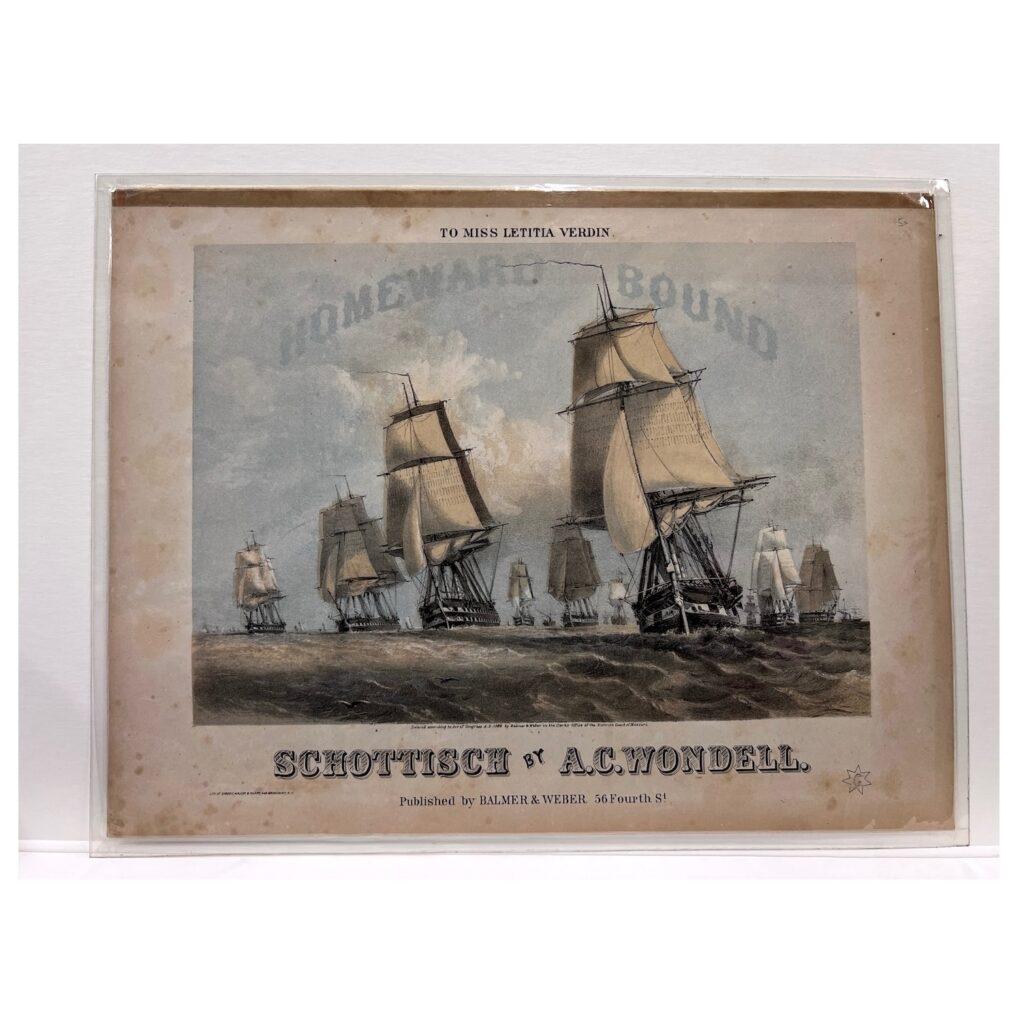

Left: Balmer & Weber, publisher; Sarony, Major & Knapp, lithographer. “Homeward Bound Schottische” 1863 (copyright date). Seamen’s Bank For Savings Collection, 1991.077.0100.

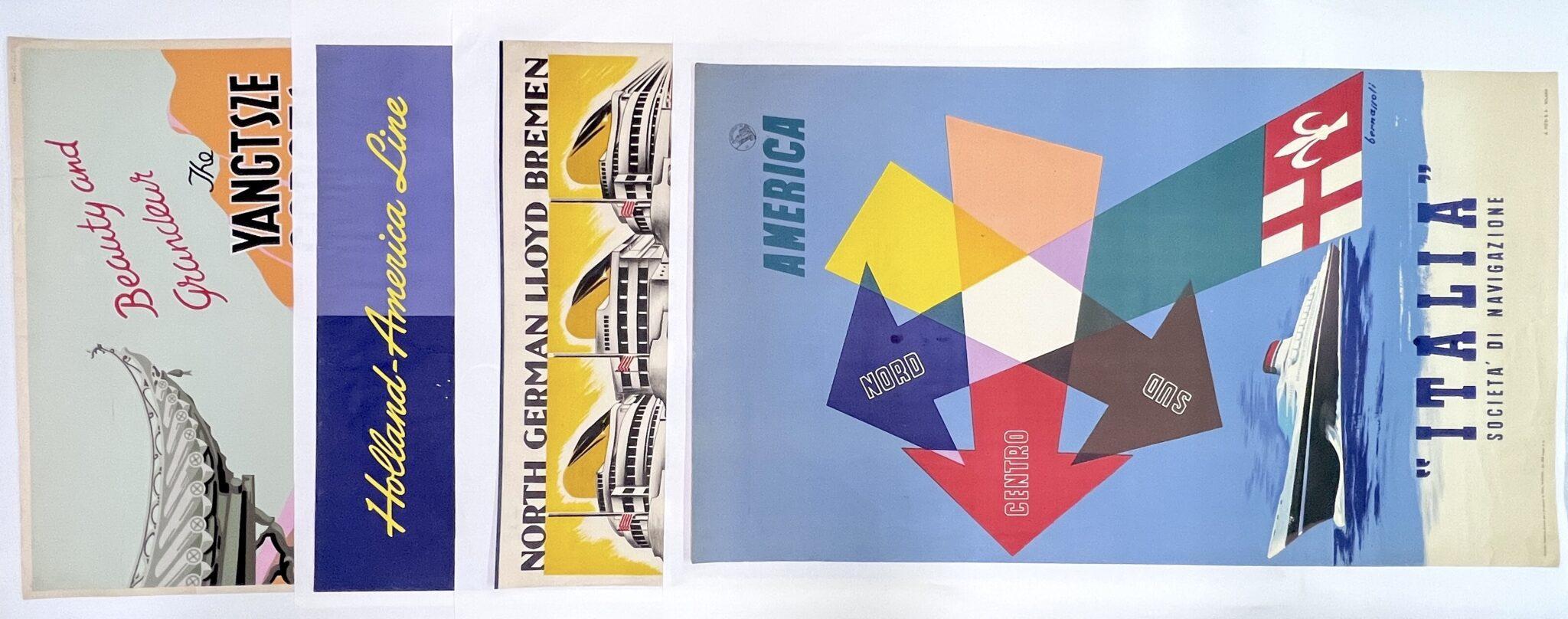

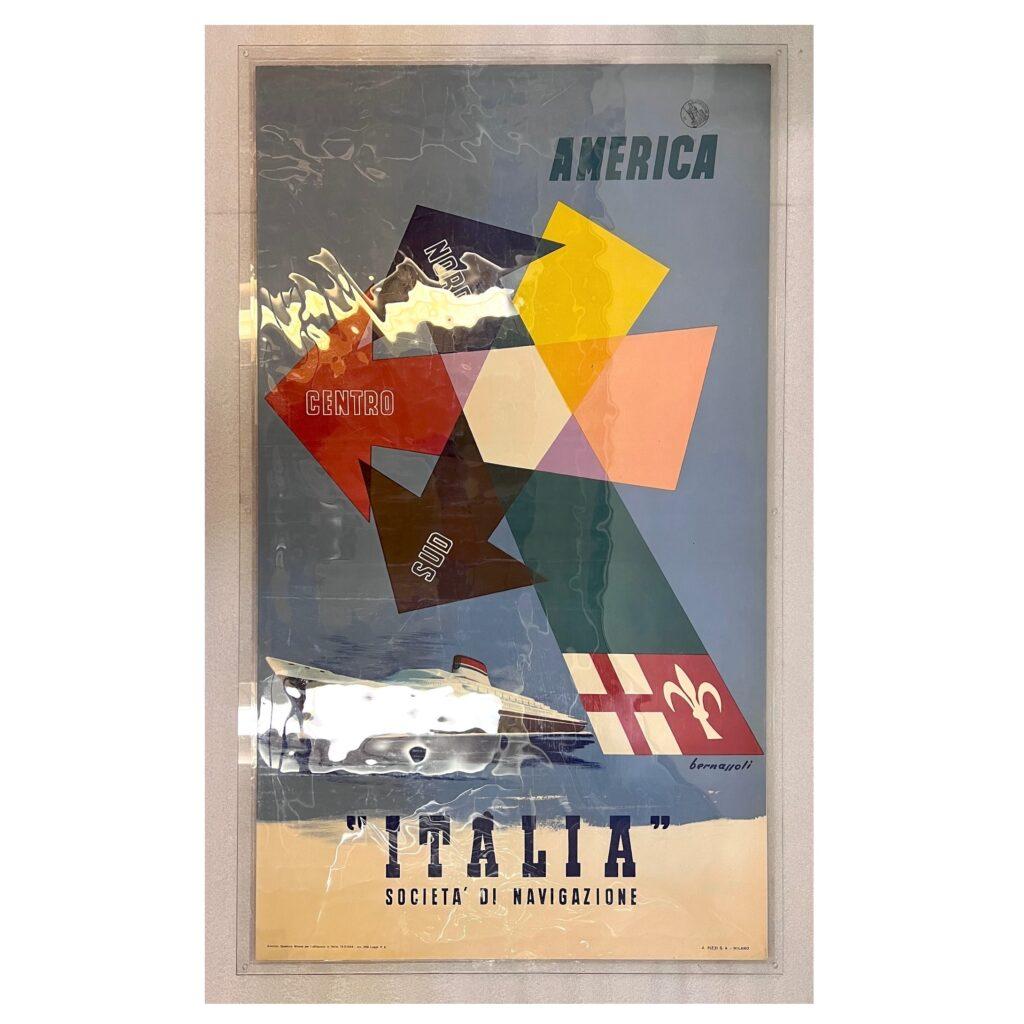

Right: Dario Bernalozzi (1908-1999), artist. A. Pizzi, printer. “Italia, Societa di Navigazione” ca. 1951. Der Scutt Ocean Liner Collection, 2001.028.0113.

Images of collections items encapsulated in plastic, pre-treatment.

We do not have an accurate estimate of when the lamination took place, but as the objects remained encased and the plastic began to destabilize, more and more chances for loss occurred.

Several of the laminated objects, especially the clipper cards, experienced mildew and mold growth. Close to the edges of the clipper cards and the sheets of music are noticeable outlines made from chemical adhesive used during the lamination process. The conservators noted that removing and separating the plastic sheeting without causing further chemical reactions or static cling would take specialized tools and time. Finally, some minor damages on the paper pre-lamination, such as creasing that sat for an unknown number of years without breathing, caused further damage.

From Summer 2023 to Spring 2025, I delivered the group of selected objects to Alvarez Conservation Services. From the conservators’ initial on-site assessments, as well as their more in-depth analysis of the objects’ conditions at the studio, each collection and individual object were given a condition report (which details each object’s structural and visual condition) and a conservation plan (proposing the best way to safely remove and possibly repair each object).

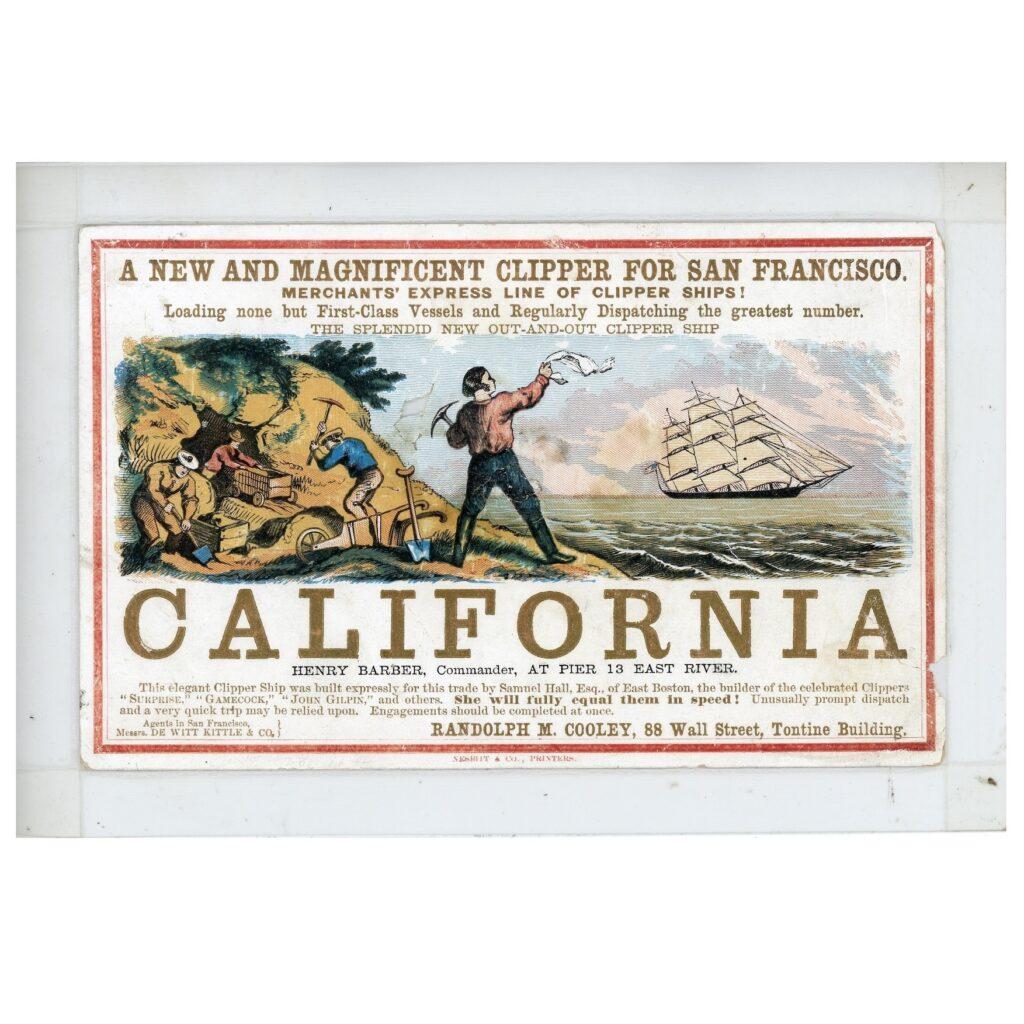

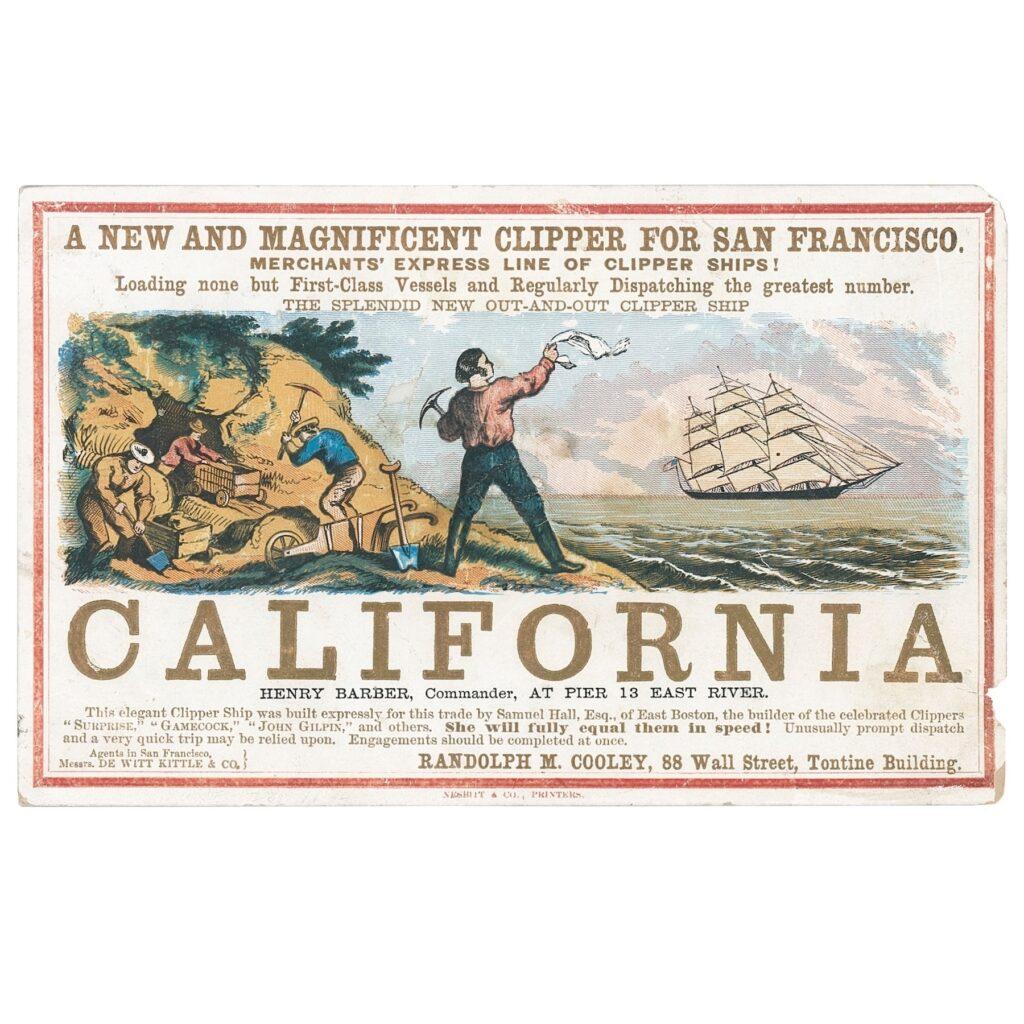

George F. Nesbitt & Co. (1832-1912), printers. “California Clipper Card” June 1864. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation, 1991.070.0323.

Images of the item before treatment, after treatment, and being installed in a case as part of the exhibition “Maritime City”.

Thanks to the meticulous work of these conservators over the course of four weeks, all objects were successfully delaminated, and for the first time in probably many decades, these paper-based artifacts were able to “relax and breathe.” Today, you can see some of the results in person as many of the delaminated clipper cards are on view in the exhibition Maritime City!

Modern Conservation Studio

During my most recent trip to the conservation studios, the Studio Manager and Registrar, Tyler Lentini, gave me a quick tour of the space. He showed me the equipment being used by the conservators for the various projects they are working on. Let’s take a closer look at what is found within a modern conservation studio.

A photography station is important to show the difference in objects between pre- and post-treatment. If you look at the table, you can see a brush to clear away any extra debris, a tape measure for taking dimensions, and a color checker to ensure the photos match true universal colors.

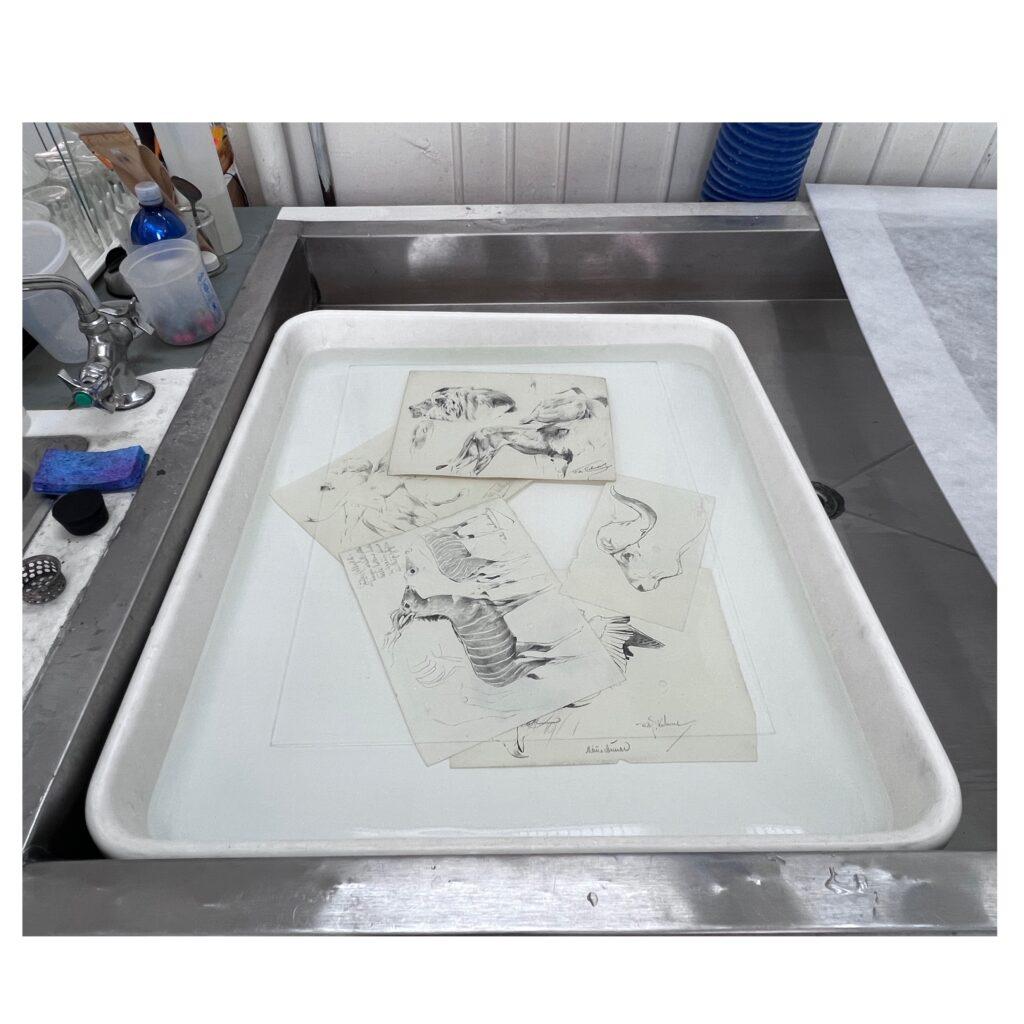

Knowing all the damage that can occur to paper because of water such as staining, mold, and distortions, it was a bit jarring to see an open tub of water while walking through the studio. But, it turns out, water is an invaluable tool used in paper conservation, as it can help to break down or neutralize acids in the paper, leading to a cleaner, brighter looking object.

Left: Works of paper submerged in a tub of water for conservation treatment.

Center: Works of paper undergoing humidification treatment beneath this table.

Right: A scalpel used to remove unnecessary adhesive from water-treated artwork.

Water can also be used to relax paper through humidification. With this table, water vapor is controlled and slowly introduced into the paper, to assist in removing creasing and folds in the object.

Scalpels aren’t just used for medical surgeries, but in the case of conservation, are used for the cutting, trimming, and removing harmful materials on documents. Here is an in-progress removal of previous adhesive tapes around the border of different artworks.

Finally, to ensure flat works return to their owners as actually flat, a finishing or lying table like these are used. Conservators use controlled pressurized weights atop a barrier board to flatten out artifacts. Different sized tables are used for different sized works.

Conclusion

If an aging artifact starts to show signs of deterioration or is damaged due to an accident or incident then it relies on the observations of museum collections management staff or anyone who owns and takes care of the piece to notice the issue.

Continuous inventory, routine condition reports, and the general monitoring of storage spaces allow cultural heritage workers to keep an eye on individual objects and whole collections. Keeping up with updated conservation discoveries and upgrades in material use is also key to long-term preservation.

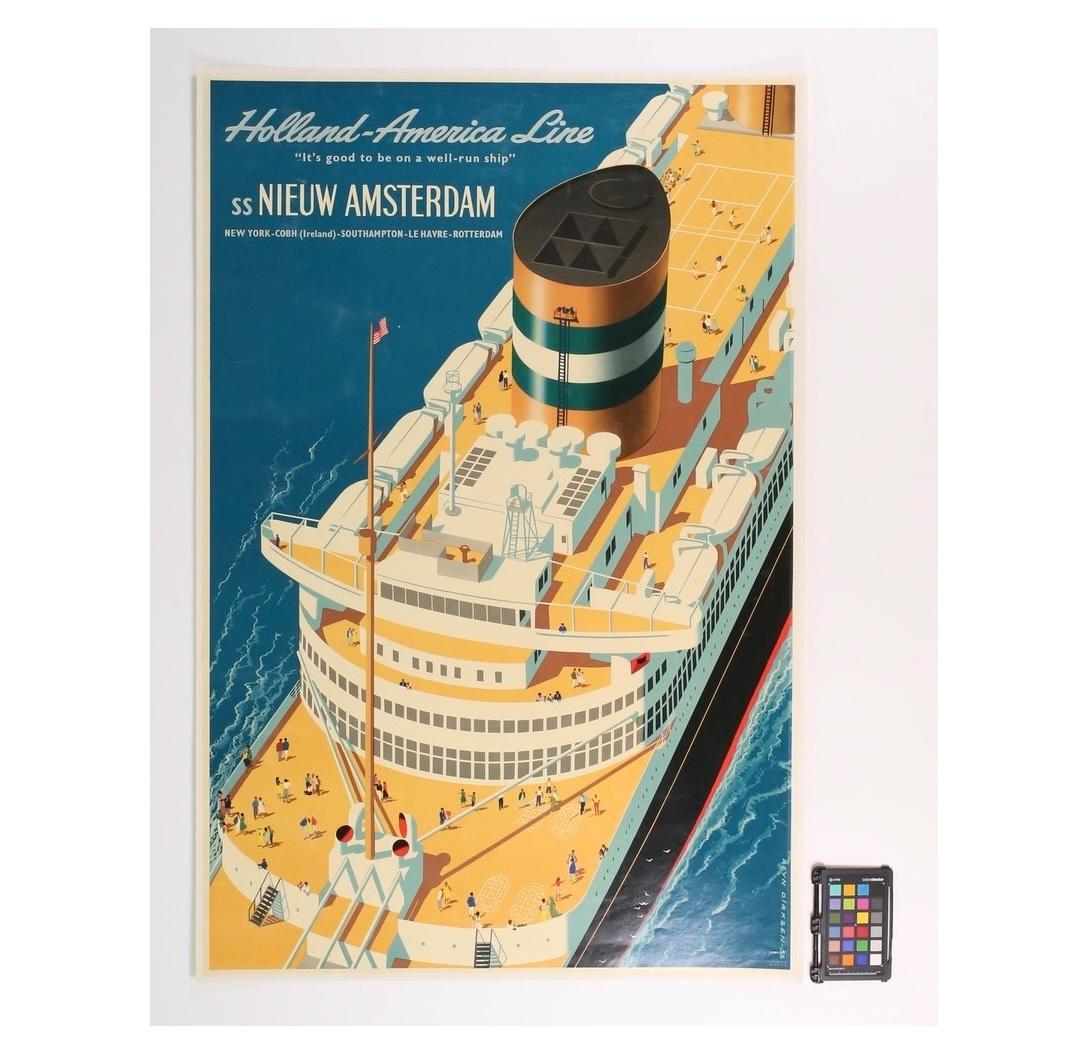

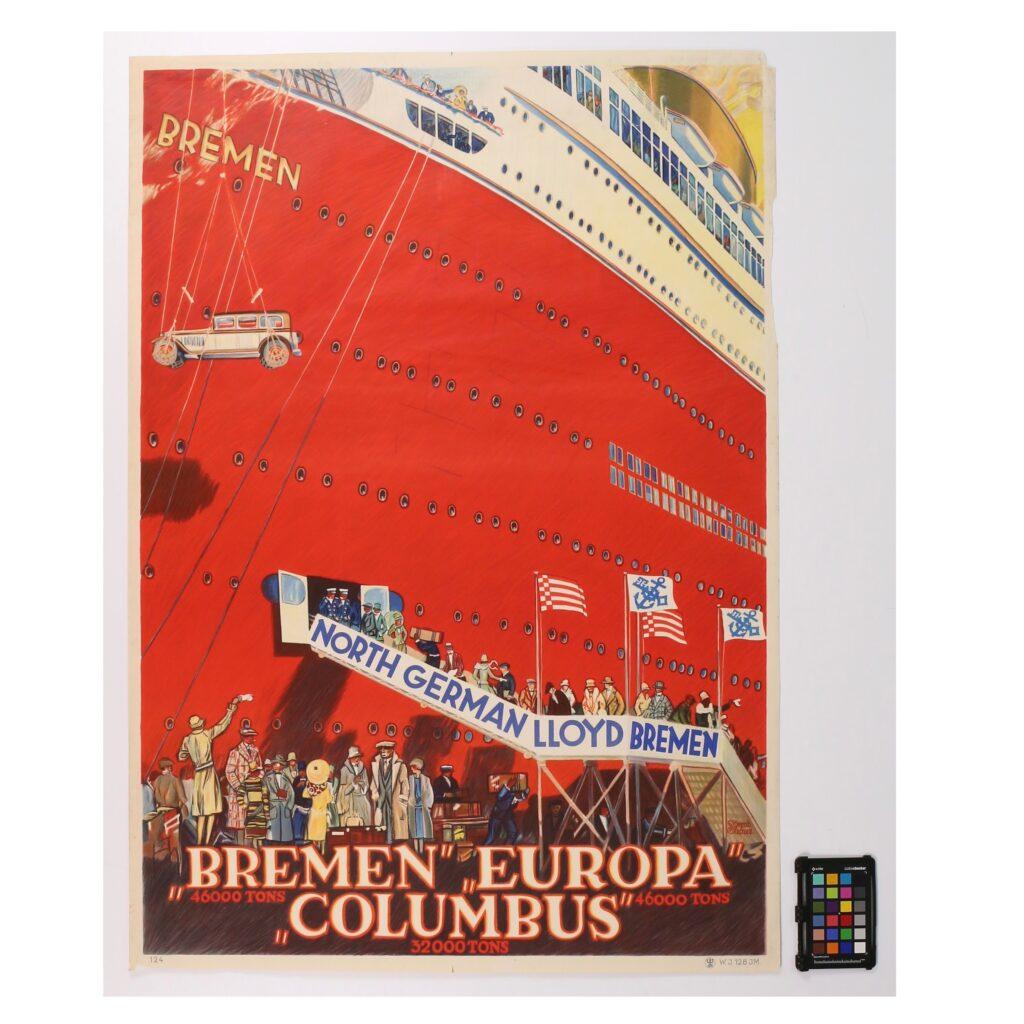

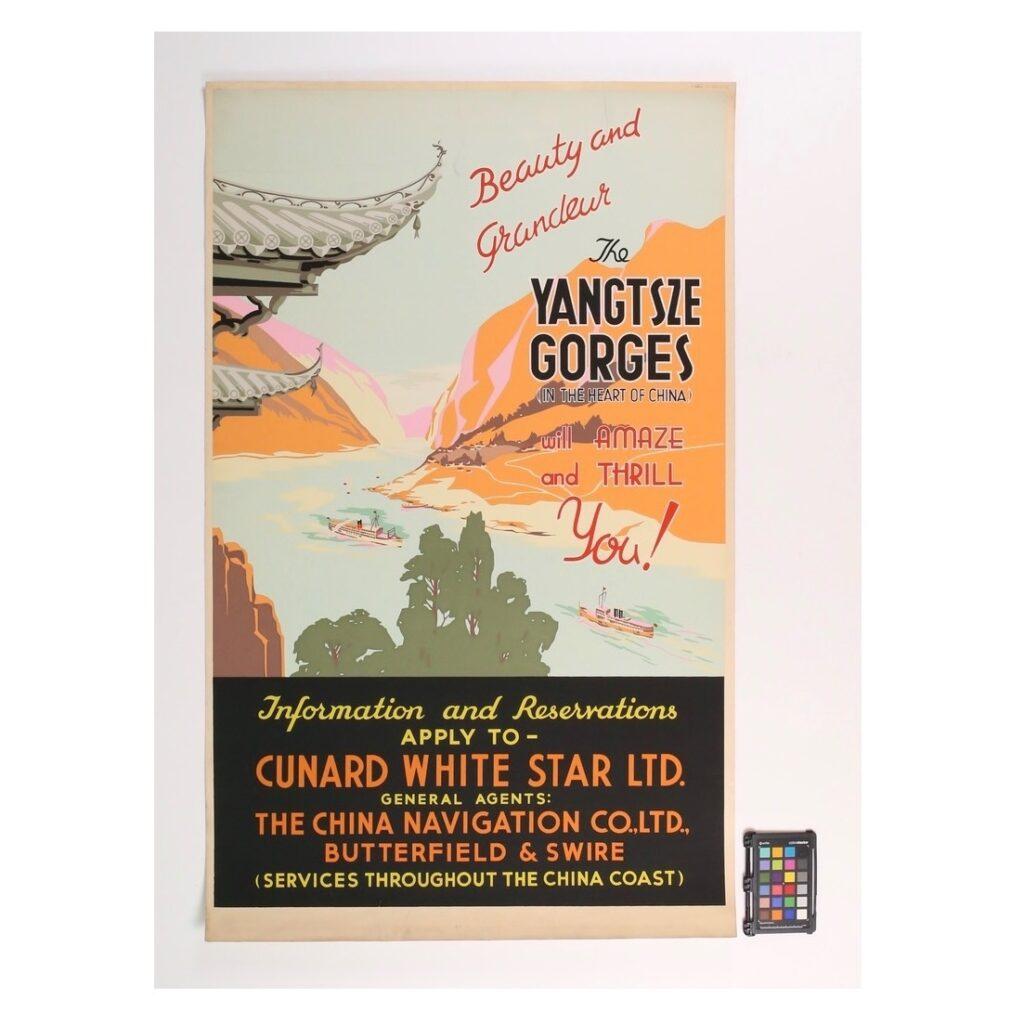

Thanks to the recent inventory and cataloguing work of Collections and Archives staff and its interns, the Museum has been able to seek the assistance of conservators to treat a selection of paper-based artifacts. The sheet music, clipper cards, and ocean liner posters have been properly rehoused since being removed from the harmful plastic and appear to be in a better physical condition than before. With a keen eye you may even be able to spot which of the Clipper Cards were recently delaminated by conservators on the free-to-access Collections Online Portal. While exploring, take a look at the newly added Ocean Liner Travel Posters highlights, too!

Left: Reyn Dirksen (1924-1999) artist. “SS Nieuw Amsterdam” ca. 1953-1954. The Robert L. Mink Collection, 2001.036.0011.

Center: Bernd Steiner (1884-1933) artist. “North German Lloyd Bremen” ca. 1920-1930. The Robert L. Mink Collection, 2001.036.0003.

Right: “Cunard White Star, Service Throughout the China Coast” n.d. Der Scutt Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation, 2001.028.0182.

Additional Reading and Resources

“What is Conservation?” American Institute for Conservation, 2025.

“How to Choose the Right Plastic for Your Project” Gaylord Archival, 2025.

“Second Lieutenant Sheldon W. Keck (US Army)” Monuments Men and Women’s Foundation, 2025.

“Caring for the Met: 150 years of conservation” by Deborah Schorsch, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 1, 2022.

“Selecting Materials for Storage and Display” Conservation Center for Art & Historic Preservation, Summer 2020.

“Paper and Water – Friend or Foe?” by Emilie Duncan, The Mariners’ Museum and Park, May 22, 2020.

“The Age of Plastic: from parkesine to pollution” Science Museum, October 11, 2019.

“Deterioriating Plastic Threatens to Ruin Museums Treasures” by Sarah Everts, Scientific American, April 1, 2016.

Ask a Conservator, series from The Brooklyn Museum.

References

| ↑1 | ”Safe Plastics And Fabrics For Exhibit And Storage” Conserve O Gram, August 2004, Number 18/2 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Oxidation is a chemical reaction in which molecular components of paper begin to weaken when exposed to oxygen, causing yellowing and decay. |

| ↑3 | It must be noted that due to this static charge, polyester film is not good for housing works of art on paper made with charcoal, pastels, chalk, or watercolors as these substances can easily lift and scratch the paper from inside the sleeve. |